The Rescue of Andromeda was the 'look at me - I've arrived' work of Henry Fehr, modelled in plaster in 1893 when he was an assistant to Thomas Brock and exhibited at the Royal Academy.

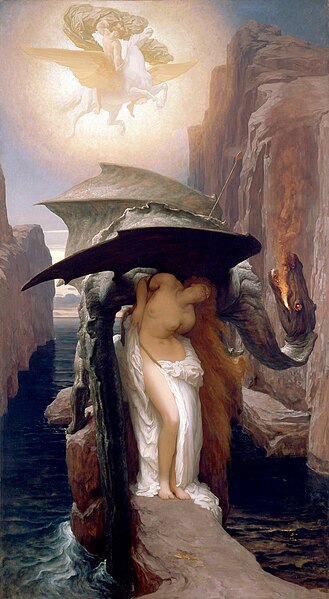

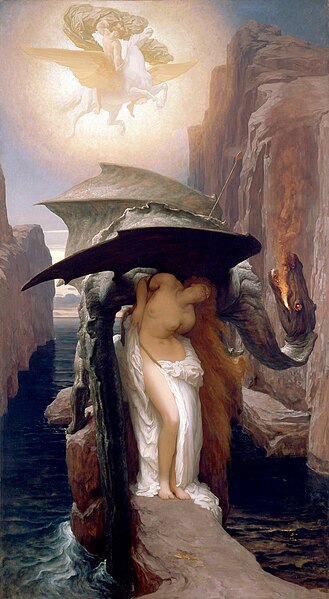

Lord Leighton, who had produced an acclaimed painting of the subject

(left), encouraged Fehr to cast the work in bronze. That version was purchased for the nation under the Chantrey Bequest.

Andromeda was chained to the rock for the delectation of Cetus, a ravening sea monster sent by Poseidon to punish her mother Cassiopeia, who had unwisely claimed her daughter was more beautiful than Poseidon's attendents, the Nereids.

Happily, who should pass by but Perseus, wearing the borrowed helmet and sandals of Mercury and holding the head of Medusa. Mercury's helmet confers invisibility and Medusa's head turns anyone who looks at it into stone, but Perseus scorns these advantages and simply stabs the monster to death. They got married and lived happily ever after.

Fehr's take on the myth is unusual. Conventionally, she is shown standing with her wrists chained behind her so both the monster and us art lovers get a good view of what's on offer.

Fehr's Andromeda is lying on the rock with the monster on top - it's as close to rape as could be depicted in art in the late Victorian period. But because it is a classical subject it seems to have raised no eyebrows at all.

Another unusual aspect is the beauty of the head of Medusa - no serpent-haired harridan she.

The statue was originally placed inside the gallery but was moved to its position to the right of the main entrance in 1911, apparently to balance the similarly-sized Dirce to the left.

Fehr was outraged. He wrote to the Tate's director Charles Aitken: "It was never designed to be placed among and swamped by heavy masonry it is quite an injury to my work. Many times I have been complimented by judges of Art – and among them personally by Lord Leighton, Alfred Gilbert and Sir John Millais and others; at present many have said it is a shame to have placed a statue of this description in its present position."

He obviously didn't rate Sir Charles Lawes-Wittewronge's Dirce either, calling it in a later letter "a group of a heavy description which mine is distinctly not."